Parties Dispute Termination of Contract of Sale

Culjak v Akrawe [2022] NSWSC 949 (19 July 2022)

The parties entered into a contract for the sale of land. The plaintiffs seek a declaration that the contract was duly terminated. The defendant denied that the contract had been validly terminated by the Notice of Termination. The Court, in resolving this dispute, relied upon the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW).

Facts:

This case concerns a contract for the sale of land in respect of residential property in Cobbett Street, Wetherill Park. The contract was entered into on 12 December 2020 by the plaintiffs as a vendor and by the first defendant as the purchaser. The contract provided for a purchase price of $1,550,000, including a 10% deposit of $155,000. The deposit was paid, and it became held by the second defendant as stakeholder.

The contract provided for a date of completion that was the 42nd day after the date of the contract. After taking into account of the fact that that day (24 January 2021) was a Sunday, the contractual date for completion became 25 January 2021 (see cl 21.5 of the contract). However, by agreement between the parties, the date for completion was extended to 22 February 2021. On 3 March 2021, the plaintiffs served a Notice to Complete that called for completion to take place on the PEXA platform at 12.00pm on 18 March 2021, with time in that respect to be of the essence. The settlement did not take place on 18 March 2021.

Late in the afternoon of 18 March 2021, the first defendant’s solicitor informed the plaintiffs’ conveyancer that the defendant needed until 23 March 2021 to settle the purchase. The first defendant’s solicitor also took steps to change the appointed time for settlement in PEXA to 23 March 2021.

On 22 March 2021, the plaintiffs, by their conveyancer, served a Notice of Termination of the contract upon the first defendant. The notice referred to the default of the first defendant in completing the purchase in accordance with the requirements of the Notice to Complete and stated that the contract was thereby terminated and the deposit forfeited to the plaintiffs.

The plaintiffs seek a declaration that the contract was duly terminated by them on 22 March 2021, and an order to the effect that they are entitled to the deposit of $155,000. (The deposit, formerly held by the second defendant, has since been paid into Court.) The plaintiffs also made a claim for damages against the first defendant for breach of the contract, but this claim was ultimately not pressed.

The first defendant denied the validity of the Notice to Complete. He also denied that the contract had been validly terminated by the Notice of Termination, on the basis that the plaintiffs were themselves not ready, willing, and able to complete the contract.

The first defendant seeks an order that the contract is specifically performed. He contends that in the circumstances of the case he should be relieved against the forfeiture of his interest under the contract and that the Court should order that the contract be specifically performed.

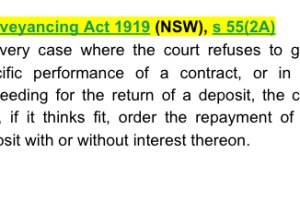

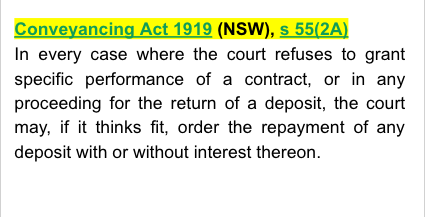

He contends, in the alternative, that the circumstances of the case are such that an order should be made in his favour under s 55(2A) of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) for the return of the deposit. The proceedings against the second defendant were discontinued following the payment into the Court of the deposit.

Issue:

Whether or not the plaintiffs are entitled to recover deposit.

Applicable law:

Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW), s 55(2A) - provides that in every case where the court refuses to grant specific performance of a contract, or in any proceeding for the return of a deposit, the court may, if it thinks fit, order the repayment of any deposit with or without interest thereon.

Demagogue Pty Ltd v Ramensky [1992] FCA 557; (1992) 39 FCR 31 - provides that the failure to disclose could be regarded as akin to misleading conduct by silence.

Harkins v Butcher; Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2002) 55 NSWLR 558; [2002] NSWCA 237 - provides that it is not necessary to demonstrate special or exceptional circumstances in order to justify an exercise of the discretion.

Havyn Pty Ltd v Webster (2005) 12 BPR 22,837; [2005] NSWCA 182 - created a jurisdiction to relieve against forfeiture of a reasonable deposit that was hitherto unknown to courts of equity.

Lucas & Tait (Investments) Pty Ltd v Victoria Securities Ltd [1973] 2 NSWLR 268 - provides that it is one thing to recognize that there is a wide discretion conferred upon the court under this section; it is another thing to determine the guidelines for the exercise of that discretion.

Romanos v Pentagold Investments Pty Ltd (2003) 217 CLR 367; [2003] HCA 58 - observed the important role played by the payment of deposits in contracts for the sale of land.

Tanwar Enterprises Pty Ltd v Cauchi (2003) 217 CLR 315; [2003] HCA 57 - focused on whether there were circumstances that would justify giving the first defendant relief against forfeiture of his interest under the contract – although the true question in this context is whether equity should intervene on the basis that it would be unconscientious for the plaintiffs to insist upon their legal right to terminate the contract.

Analysis:

The deposit (of $155,000) was forfeited due to the failure of the first defendant to perform his obligations in accordance with a Notice to Complete that made time of the essence. It has not been shown that this failure was relevantly caused or contributed to by conduct on the part of the plaintiffs.

It has not been shown that were the plaintiffs to recover the deposit, they would make a windfall or profit that in “justice and equity” they ought not to be permitted to enjoy. In that regard, it should not be overlooked that the termination of the contract occurred some 16 months ago.

Moreover, an attempt by the plaintiffs to re-sell the property later in 2021 was stymied by the lodgement of a caveat by the first defendant. The basis of the caveat, being the existence of a contract for sale, has not been sustained. The first defendant has not established that his failure to complete the contract by 18 March 2021, which was a breach of the contract in essential respect, was relevantly caused or contributed to by conduct (including silence) on the part of the plaintiffs. On 11 March 2021, the plaintiffs maintained that the contract was required to be completed in accordance with the Notice to Complete, which made time of the essence.

The first defendant could not safely proceed on any basis other than that a failure to complete by 18 March 2021 would entitle the plaintiffs to terminate the contract. If the first defendant had the necessary funds, there was plenty of time to make them available on the PEXA system in readiness for a settlement on 18 March 2021.

The evidence given by Mr. Akrawe does not explain why that was not done. He does not say, for example, that he delayed doing so because of a belief or hope that the proposed new contract would proceed instead of the existing contract. The fact that he was “shocked” when the plaintiffs did not proceed with the new contract suggests that he may have had such a belief or hope, but the effect that such a belief or hope may have had upon his conduct is not explained.

Conclusion:

The plaintiffs are entitled to recover the deposit after validly terminating the contract for the first defendant’s breach. The claim for the return of the deposit is dismissed.